TR-49 review: sorry, I'm not up to code

I feel like my brain is broken. Sci-fi mystery puzzler TR-49 is the exact sort of clue-hunting solve 'em up I normally love. But somewhere in its thorny forest of fictional author names and twentieth century dates I got lost, hacking my way through more with frustration than curiosity.

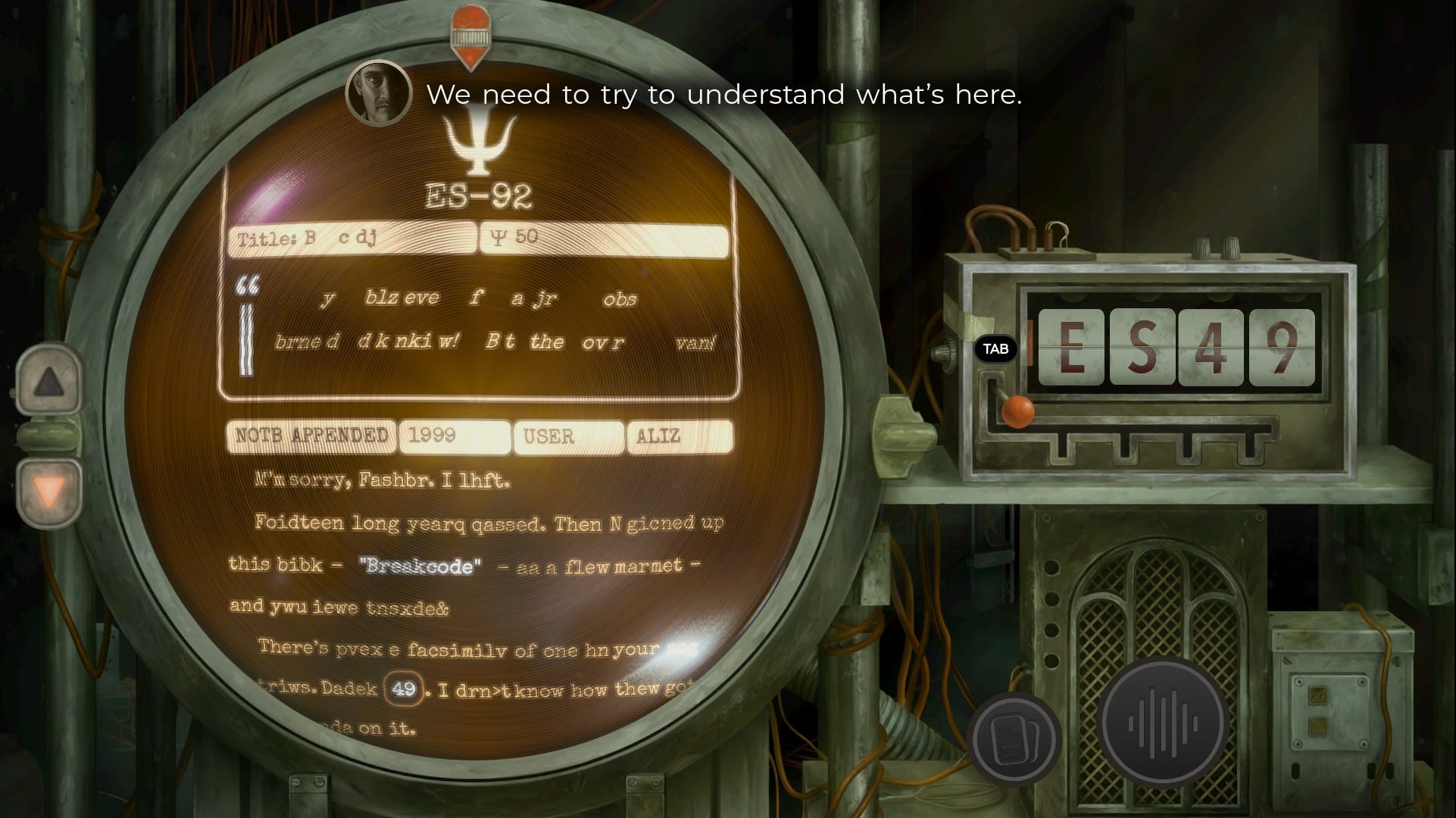

It's packaged as a codebreaking game, but really it's a "database game". Imagine Her Story in an alternate history. You type codes into an odd machine to reveal snippets from books or journals. You're here to find a particular book. But the texts you discover are mostly the jumbled notes from previous users of the machine. Sounds intriguing, and many scribbles display a great range of writing styles. But I found slowly constructing my understanding of the plot and its many characters more cumbersome than rewarding. Putting its cryptic story together felt like building a cathedral out of SQL.

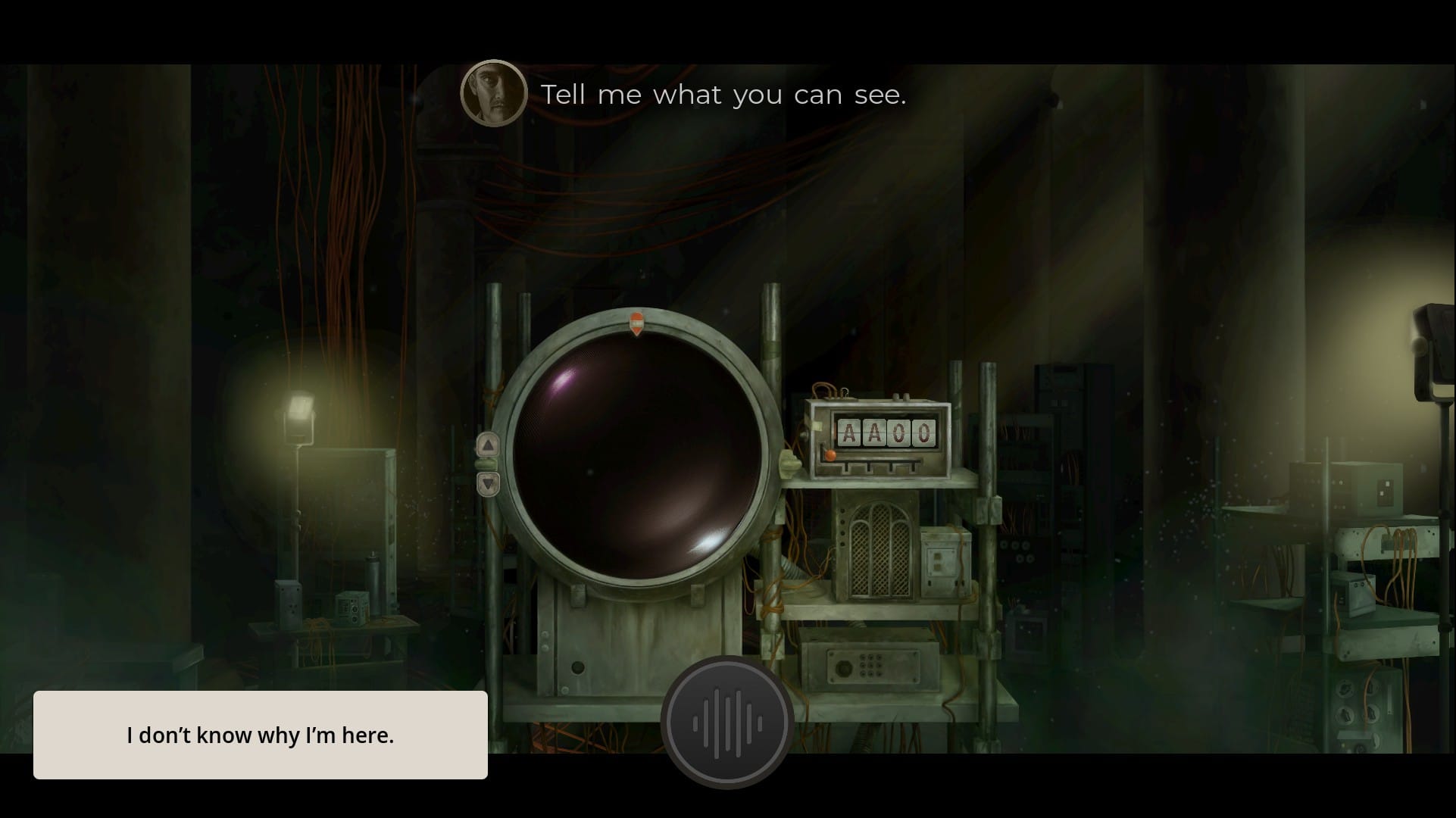

Some basics. You're Abbi, and you're stuck in a dank cellar with the strange machine. A voice comes over the radio, a bloke called Liam, who asks you to start toying with the levers and dials on this weird old codebreaker.

"We don't have time to spare on mysteries," says Liam, refusing to reveal any of the circumstances in which you find yourself, including who you are or why you remember nothing. I can tolerate an amnesiac protagonist as much as the next player, but maybe not for as long as TR-49 drags it out. Eventually, you learn you are here to look through this machine for this one book. You don't know the author or the date it was written or why it's important or why Abbi is the one required to do this. All you know is the book's title: Endpeace.

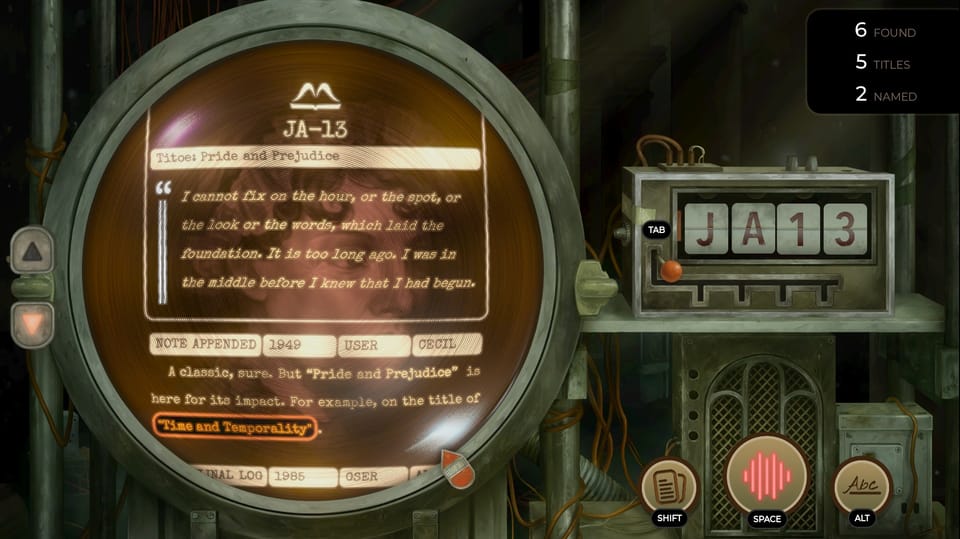

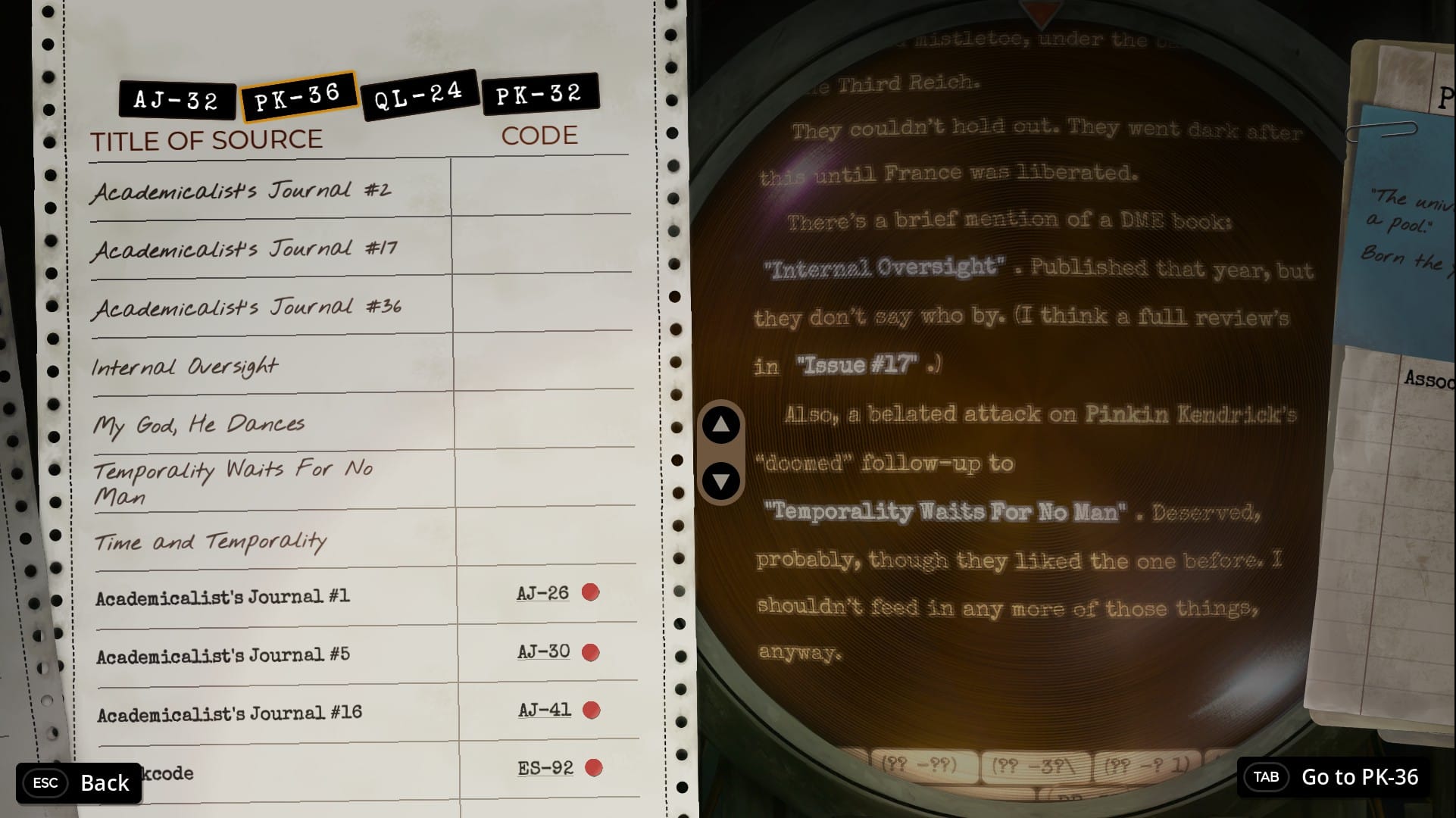

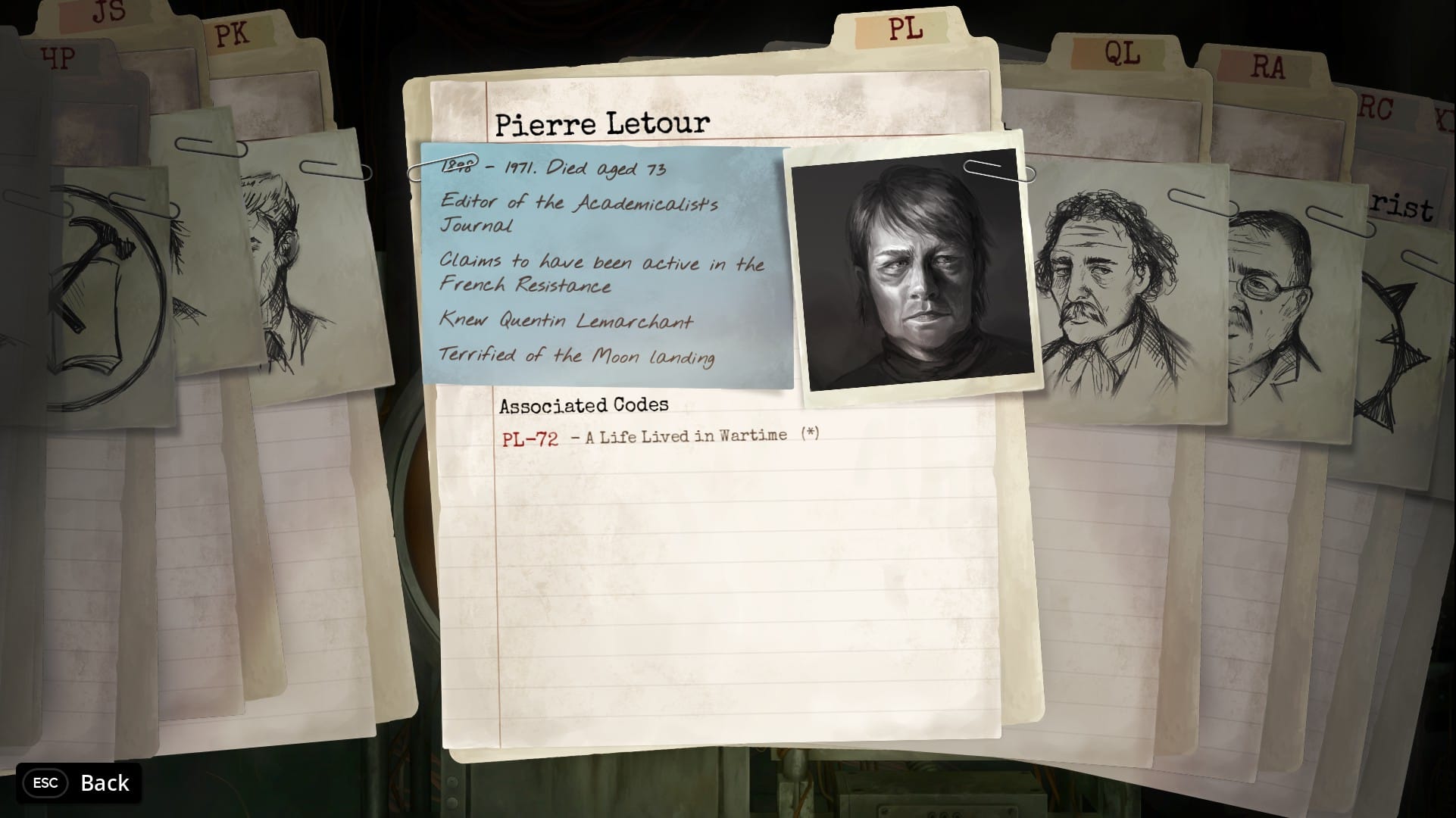

Other reviews have steered away from spoilers. I'm not going to try too hard to avoid them, because to understand my misgivings you'll have to understand some of the game's inner workings and patterns. For example, you quickly learn that codes to unlock new notes are (mostly) constructed using an author's initials, followed by the date of publication. So a tome on quantum physics written by Joshua Silverton published in 1929? That's JS29. The memoirs of egotistical occult fan Pierre Latour published in 1972? That's PL72. We've all been taught Dewey decimal, it makes sense. Alongside these fictional authors, a real author might sometimes appear - which is why JA13 leads you to an entry on Pride and Prejudice.

And that's the gimmick: an entry on Pride and Prejudice. Not really the book itself. TR-49 is a game of secondary sources, not primary. Aside from a sentence or two of flavour text (more concerned with establishing the voice of the author than any fact or opinion) you do not read the works of Quentin Lemarchand or Dorethea Pemberton or any of the unseen characters repeatedly touted as geniuses in the user notes. You read the marginalia about them. Sometimes you're removed even further from the source, such as when you're reading notes about literary journal articles who themselves talk of authors.

This is a metatextually fun idea and I love it. In our real world, Flann O'Brien's novel The Third Policeman has many footnotes about a scientist called De Selby and his arguments with other fictional scientists. Throughout that novel the reader builds an idea of a mad academic. TR-49 is like solving a jigsaw made out of O'Brien's footnotes. Except there are, like, twenty De Selbys.

If you are rolling your eyes at my references to - ugh - real books, then you might need to walk away. TR-49 is deeply literate and thematically tight. Early in the game Abbi quotes from Tennyson poem The Lady of Shalott - a damsel in a tower who can see only reflections in a mirror, never looking directly on what is happening in the world. Abbi, we'll learn, is stuck in her own "tower" of research, never seeing the reality of the world, only the commentary about it. So it makes sense that she sees only secondary opinions and reconstituted ideas, never the source, never reality.

But as a player, without those primary sources, I rarely felt like I could build a solid body of understanding. I wanted something hard that I could stick my climbing axe into, or at least some single author to connect with, some real reason to keep digging for Endpeace. This is a game driven completely sans context. That is by design, I think, but obfuscation doesn't necessarily equal mystery. Her Story is a "Who-dunnit?" Obra Dinn is a "Who-What-Where-How-and-Why-dunnit?" TR-49 is basically a "Who-Wrote-It?" But you don't know what "it" is and soon you won't know what "writing" is either.

The fragmentation frustrates me. I want to hold and read a full copy of "The Academicalist's Journal", not just notes about it. Second-hand information feels less weighty, less reliable, like I am basing my puzzle solutions on a screenshot of a dungeon, instead of exploring the 3D space itself.

The player is repeatedly told this book or that book is important or influential, but the content of those books is kept to a minimum. You must accept or reject the cryptic and scattered interpretations of previous users of the machine. Conceptually, I love this idea - an entire game of unreliable narrators! In practice, I can't stand it. A knowledge-based puzzle game in which knowledge itself is unreliable. This is a commentary on our own post-truth world. It also gives the storytelling a free pass to be as contrived as it likes.

That's not fair, there are some concrete facts to pin down. Mostly, dates of birth and dates of death. Any mention of a year becomes an important anchor. Because most codes use a year of publication, ages of characters become significant. Historical events like the second world war need to be taken into account. For anyone who dabbles in Ancestry.com, it's probably a familiar feeling. Unfortunately, I can't stand doing date-of-birth arithmetic even for my own dead relatives, so the principle puzzle of TR-49 just made me feel a bit bored and mentally tired. It also reveals that a key activity of the game has nothing at all to do with the human element of mystery solving. It's just doing sums. The main verb in TR-49 is not "deduce" as much as it is "add" and "subtract".

I don't find this particular method of discovery that interesting, and given the literary bent of the rest of the game it causes the opposing hemispheres of my brain to have a tantrum at one another. Imagine reading a detective novel that has a basic maths captcha on every other page. I realise this may say more about my own mathematical laziness than the game itself.

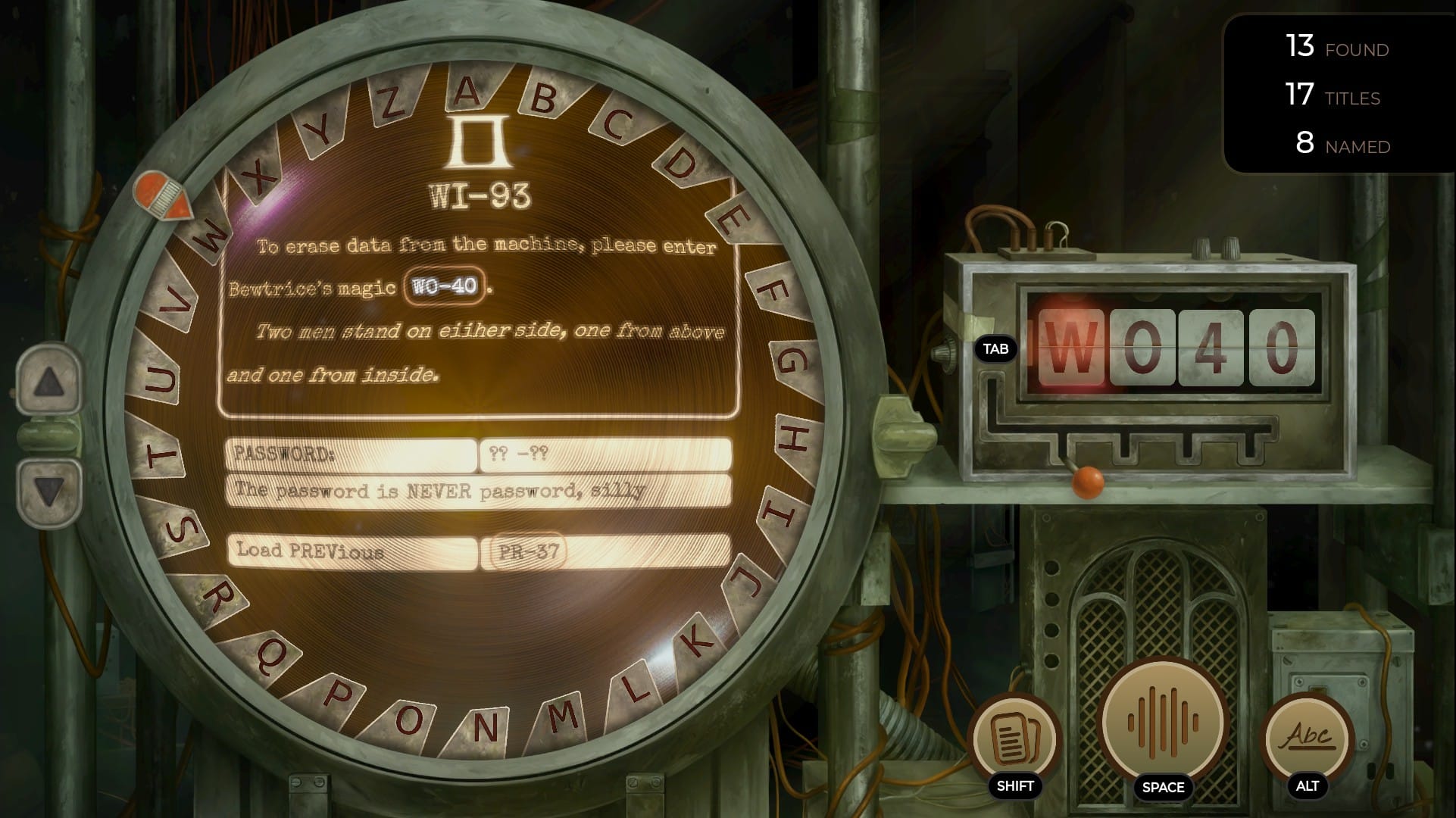

This reliance on year-codes has a bigger impact than just turning off the dyscalculic among us, though. It means you quickly realise a cheesy mechanical solution to find any publication - bruteforce the codes. For example, if you know an author published books between the year 1911 and 1950, all you have to do is punch in their initials and then the numbers 11 through 50. The game's design suggests this is not the "correct" way to play. Enter too many incorrect codes and you'll soon notice that text which was once legible becomes rescrambled, difficult to read, alx tge sentinjes jet gumplid yp.

I'm still figuring out what to make of that design choice. Does the game want the player to use bruteforce guesswork or not? My guess is: yes, but not too much. It is flavoured as a codebreaking game, and codebreaking is often an act of algorithmic cracking. Meanwhile many clues will result in an explicit range of years to work from, hinting there could be a book hiding anywhere in a three or ten-year period.

But the game also wants you to be precise. It wants you to engage with the notes, read thoroughly, make inferences, draw conclusions. It wants you to aim for understanding, and so it polices you into this by making texts unreadable if you brutey brute too much. For a game that necessarily involves guesswork and tons of re-reading, this feels like an act of punitive whimsy (there's a secret code to "heal" this scramble-damage - HE47 - you're welcome).

Often in a puzzler like this, the frame story provides some structure, some solid perch from which to peck at the unknown. But the mystery of your character, Abbi, and her radio handler, Liam, feels as abstract as anything else you are doing.

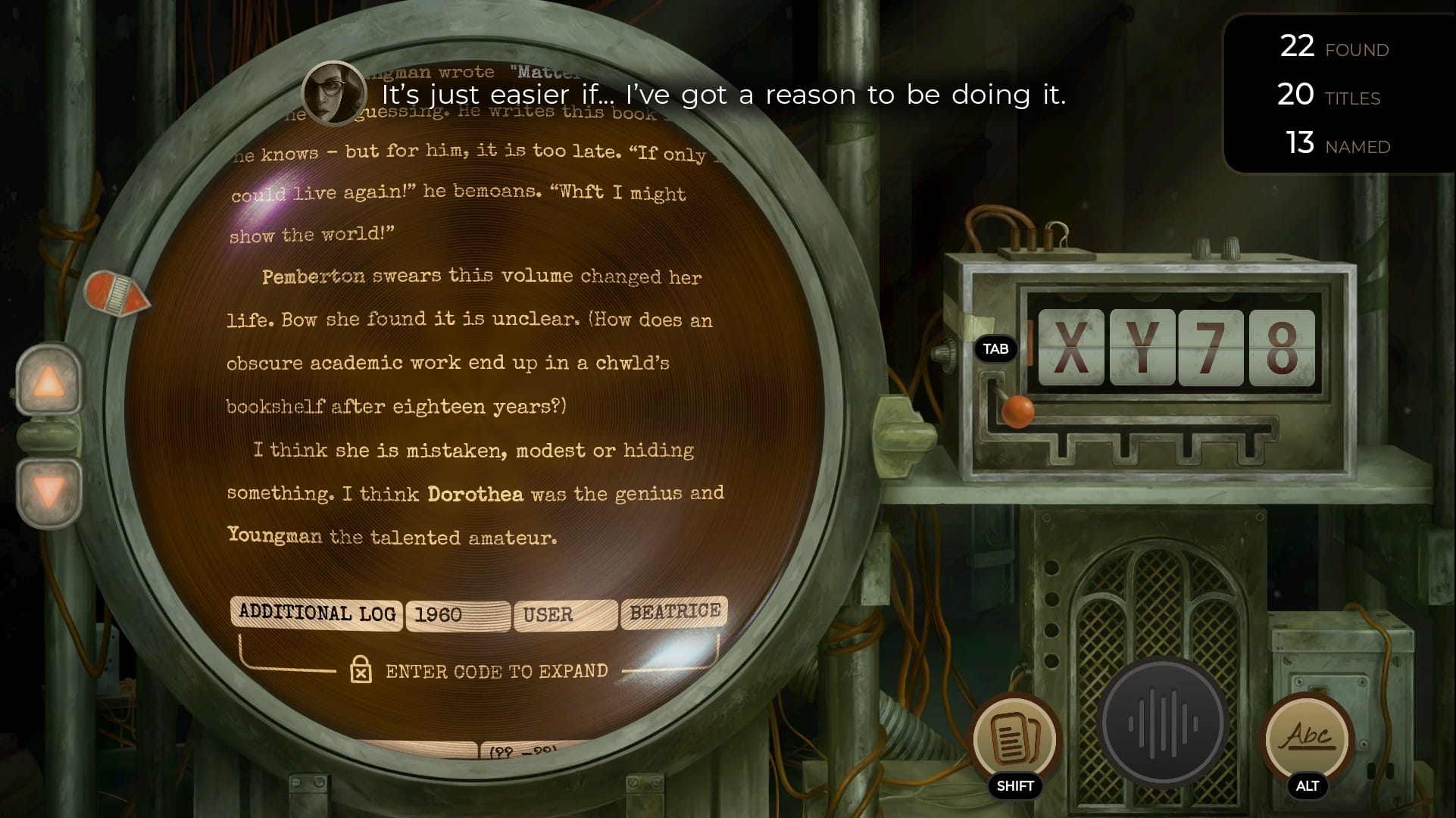

"It's just easier if I've got a reason to be doing it," says Abbi at one point, annoyed that Liam repeatedly refuses to explain the circumstances of her entrapment as she trawls through the database. Honestly, I felt the same way for much of the story - mystery alone can motivate me, but there is a species of coy mystery story in which revelation is obscured in increasingly contrived ways. TR-49 isn't as bad for this as, say, Lost or The OA, but it has some of the same sensation to it. Again and again I asked myself - why is this important? - and with every note that failed to answer this question, every radio call that only raised more questions, I grew more impatient. All breadcrumb trail and no loaf.

Well, maybe half an old baguette. The game eventually gives you a little bite of nourishment, for me it happened about four hours into its six-hour story (your mileage may vary, there's no set order of revelations). I realised what was happening in this wordfully warping sci-fi world, and the significance of the books (and your ability to manipulate them) became clearer. But reaching this moment was a meander through disconnected strings, and the ending that followed didn't make me feel clever, it simply rewarded another guess.

Boredom sometimes comes of fatigue, and I think that's what happened to me. The game requires you to have the mental bandwidth to carry a big cast with a lot of interlocking and overlapping connections, a red string brain that is happy to hop from one page in a notebook to another. In this, it alienates me, because I am a focus guy. One book at a time, please. Having so many simultaneous loose ends overwhelms me. I am the same when faced with a metroidvania with 20 possible paths to go down. Paralysis. Give me, like, five. I can deal with five.

Looking at 18 folders of names, with one or two details scribbled on each, doesn't even feel the same as being presented with, for example, the ship's crew list in Obra Dinn. Because in Obra Dinn you can at least spatially focus on one physical location at a time. In knowledge-based explore 'em up Outer Wilds, your focus comes of an apocalyptic deadline, you can only explore one planet at a time. TR-49, by contrast, has only one space - your brain. It requires you to keep an entire Google Sheets document in mind, and then perform primary school sums while you're at it. Sorry, you must understand. I'm extremely stupid.

And so I'm annoyed, frustrated with both the game and myself. This is exactly the sort of puzzle I usually love, from exactly the Inkle I often admire. I adore stories about people hunting for authors (the search for Archimboldi in 2666, the run-in with Silas Flannery in IC79). So in a different format I might have loved this too. It is a smart story about the spread of literary influence, in which great concepts are as deadly as viral payloads (and mutate just as readily). It has much to say about generative AI, revisionist history, propaganda, and the collective creative loss in store for mankind - this machine eats books and vomits lies. And it is a meditation of the knock-on effects that words can have on reality even centuries after they are written. But it makes me subtract 19 from 66. And I hate that.

Obviously I'm not about to write off the studio that made one of my favourite adventures of all time in Heaven's Vault, just because their codebreaking Radio 4 audio drama made me do sums. I'm not that petty. But I will be honest: TR-49 didn't land clean for me at all. Between the audio telling one story, the marginalia telling another, and the authors telling dozens of others, it becomes a patchwork game of narrative "context switching", heavily reliant on counting years in lieu of any other puzzle. It's intelligent. It's different. It's messy. It's exhausting.

Comments ()