Hey! Listen! Here's why games use 'nag lines'

A few months ago Metroid Prime 4 was shown to press, and caused a small, localised stink in the chattosphere. We don't care much about Nintendo games at Jank, and I have no emotional stake in Metroid (Samus is the Ninty equivalent of John Halo - an extremely boring person vacuum-packed in fancy metal) but I do enjoy divining the stinklines that emanated from the first-person shoot 'n' splore, and the complaints by folks who got hands-on time with it.

The odour was familiar: a sidekick character would verbally needle you about performing the next correct action. "Samus, there's something interesting over there," a sidekick called Myles will say if the player strays too far in one direction. "Are you sure we don't need to use that?" Somebody in the resulting shiteswirl of social media discourse called this a "nag line". A succinct moniker for a trend that has existed in games for a long time without being given a name.

Nag lines are common enough, you'll know one when you hear it. Spend ten seconds inspecting a cool-looking prop while an NPC waits by a door, and they might say: "This way, McBloke, we've got a war to win!" Muse a little too long next to a puzzle without doing anything in an ancient tomb and your peppy sidekick will offer a hint. "Hmmm, those ropes look a little worse for wear."

The nag line is irritating and patronising to many of us - a transparent sign of impatience or lack of trust from the game's designers. Do the makers of Murderville VIII: More Murder really think I cannot solve this double homicide? I have played every Murderville ever released!

On top of communicating that the creators of a fictional world think you are a bozo, it can also shatter any feeling of existing in that world at all. This is especially true when the nag lines come from your own player character. "Man, better get climbing," says Jane O'Flubbnutt, with the identical self-snark of hundreds of other heroes and heroines who came before. Game protagonists are notoriously guilty of existing in two modes: they either speak to themselves constantly about the dumbest shit, or they say nothing at all.

The writer will fix it

A player's natural reaction at the nag line is to seethe at the writing. It's the writing team who put those words into that mouth, after all. The problem with throwing blame onto the scribblers is that they're often not the ones who make that decision. They are more often simply performing narrative triage to a design wound that hasn't been spotted until it's too late to do anything else about it.

"If playtesters generally get lost or cannot find their way, or haven’t solved the puzzle in what is designated a ‘good’ amount of time... it’s normal for a game designer to panic," says Cara Ellison, a former games journo buddy who has written for games like God Of War: Ragnarök.

"I will say that a lot of this panic is caused by a feeling that the people above you might not think your team has designed the level well... and so often the answer can be a last-minute ‘can you put a line in there to tell them about it?’ to the narrative team.

"This is not often ideal, but it’s because focus tests tend to come later in the production cycle by necessity..."

"A line of dialogue is often seen as a ‘cheap’ solution close to ship."

Whatever is causing players to get stuck - that should have been noticed before it gets to the point where a "nag line" is needed, says Ellison.

"Personally, I think supporting level design, puzzle design, UI or UX design and stepping in earlier and with more resources would be preferable, however these are not ‘cheaper’ solutions. A line of dialogue is often seen as a ‘cheap’ solution close to ship."

So nag lines often happen when playesters don't see the crate of ripe puzzle papayas hanging above them. Or they get turned around and don't know which of the four identical sci-fi corridors to go down. Maybe they forget where they're supposed to bring the Bawunga Core they've just found, because they were told an hour ago.

When a developer sees someone getting "stuck", they seek to fix it. But ah, deleting whole corridors or rearranging level layout will be troublesome and take a lot of the level designer's time. The cheapest and safest solution in cases like this is to get the writer to make somebody say something. And if the player character is the only person in the room? Well, they'll just have to talk to themselves.

"The Bawunga core! I gotta get this to McBlaggart! Back to Glob Street, I guess."

God Of War: Ragnarök itself got some flak for having annoying nag lines during puzzles, although Ellison wasn't the person who wrote those, she says.

"I’ve never written real nag lines that I can remember," says Ellison, "but I’ve been in the vicinity of them on many AAA projects (very few indie), and I think the problem has been that there hasn’t really been a plan for them, they are generally incredibly reactionary.

"It’s only later when people are wondering - 'Hmmm, how can I solve this? I’m stuck' - that people start to panic. I think the problem is that it’s not clear if we should be panicking at all, or whether it’s the playtest environment that we are responding to."

If you're gonna nag, at least be funny

So nag lines are sometimes panic-stricken plasters. Wordy bandages slapped onto a game in the later stages of production, because rejigging the actual "physical" parts of the game world would cost time, money, or both. But that doesn't mean they have to be done badly.

"Skin Deep has a section at the start with 'nag lines', but it's a grand total of about two or three of them," says Laura Michet, writer on the first-person sci-fi stealth caper that sees you rescuing cats from space pirates. "And they're also there to freak the player out and make them feel pressured and desperate, and to sort of just raise the temperature on the situation."

"We had to put them in because people became so profoundly lost and confused in this one tiny room that they routinely got completely turned around and would lose track of important physics objects and goals."

"I have seen people respond with irritation to Palanka's lines in those rooms, but I see it as such an important tone-setting experience that it's worth it."

If you've played Skin Deep you might know this scene. It's in the tutorial mission, and you are tasked with eliminating your first guard. But it's a multi-step process of sneaking up on them, leaping on their back, bashing their head against a soap dispenser, removing their head from their body, and flushing the decapitated head down a toilet into space. You do all this as the captain of the spaceship (a cat) yells instructions at you.

"It's such a high-pressure, deliberately cartoonishly slapstick situation where they're engaging in some of the game systems for the first time, including physics, and the systems are loud and disruptive and visually busy and overwhelming on purpose," says Michet.

"Players would just create a huge mess and get completely distracted once we let them loose to engage with the systems, so once they've exhausted their first goal, we decided to start having the NPC yell at them about what to do next."

It didn't just clear up the confusion, it made the stressful moment funnier too.

"If we hadn't had them in there as 'nag' lines about their next objective, I probably would have campaigned to make the NPC in question, Captain Palanka, yell at you over and over anyway, to make you feel like his situation was urgent and silly.

"I have seen people respond with irritation to Palanka's lines in those rooms, but I see it as such an important tone-setting experience that it's worth it. And they're generally only annoyed for a couple moments while they get their bearings and free themselves of the spell of physics chaos."

We've been here before

Even if done well, the nag line is often there because you, the player, need to be shown or taught something with explicit force. This might be because the game simply cannot do that in a wordless way. Or the designers have decided it's too much effort to do so. Which is why nag lines most often show up in tutorials or early levels.

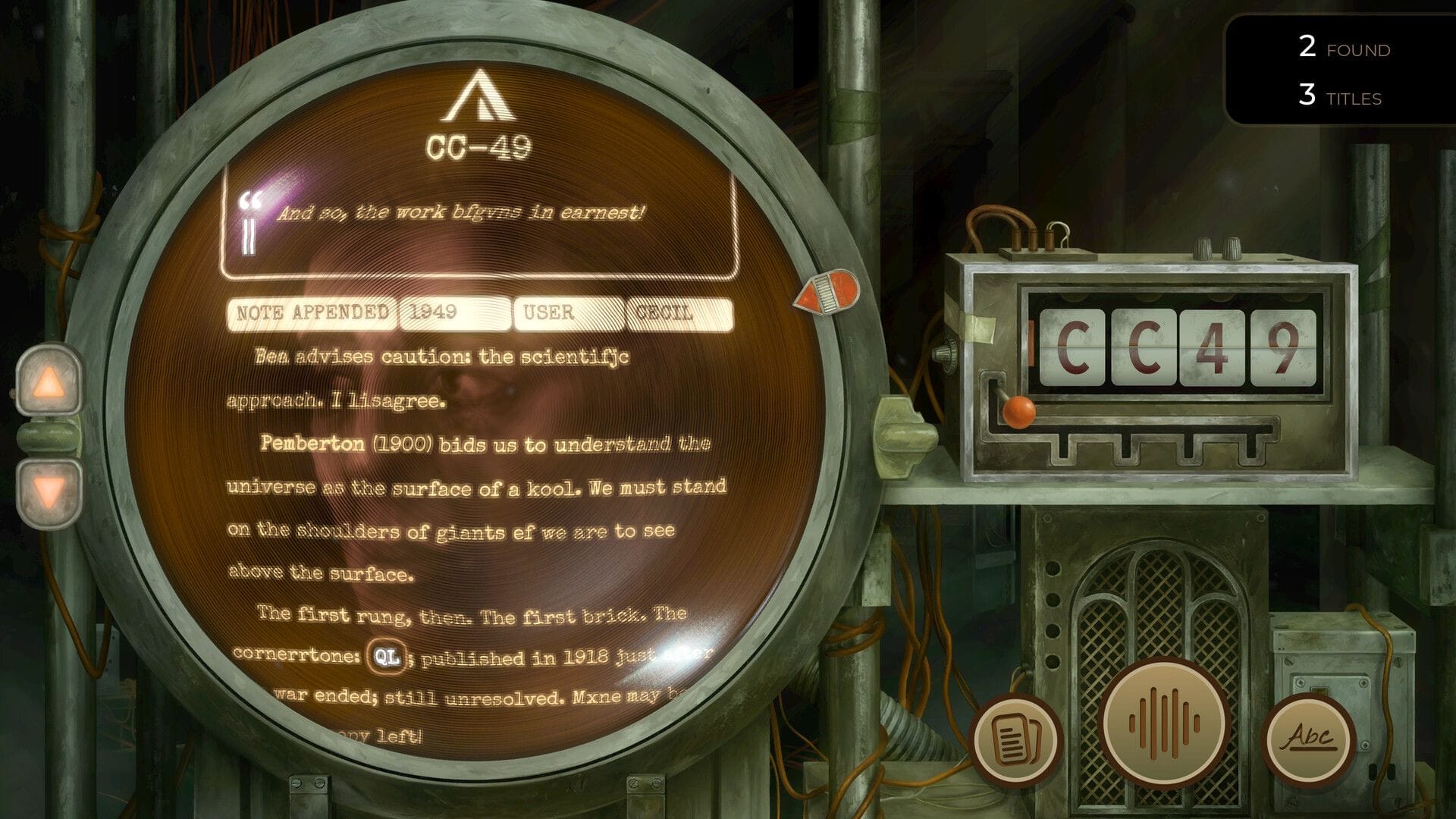

"I think the nag line things happen when either the mechanic you're teaching just isn't consistent enough for a player to master (so like climbable ledges requiring yellow paint...) or when the tutorialisation isn't given enough room," says Jon Ingold of Inkle, writer of sci-fi adventure Heaven's Vault and the recent codebreaking game TR-49.

"Building a game that unfolds one small piece at a time is a really, really difficult constraint. The nag line is a sticking-plaster over that problem."

"Some games are masterful at teaching mechanics, but when you look at the very best examples - Portal, maybe, or Journey - one notable thing is they take the time to employ the entire design space of the game just to teach one button, or one idea. Tutorialisation isn't an afterthought in these games, it's a core deliverable of a chunk of the game."

The reality is that games are not the sole offenders when it comes to this type of hand-holdy tutorial writing. We see nag lines in TV shows, film, and novels, but we don't call them "nag lines" - we call it shitty exposition.

"Books, films, theatre, games; they all use the same basic tools," says Ingold. "The problem with the 'nag' line is rather a problem of factual exposition, which is basically impossible to do using subtext in any medium.

"When Elrond says, 'take the Ring to Mount Doom, drop it in' - he has to say exactly that or we don't know what's going on. 'Now would be a great time to press the X button' is the same category of writing - it's just that games require us to know the system almost all the time, in a way that movies or books largely don't."

In other words, when a sci-fi novel unfurls a passage of exposition to remind you about a character's traits or their part in the great Flubbotech War of 2967, it might feel annoying and patronising. But when a game character tells you to "try the lever over by the cage" you get the additional irritation of being nagged, because after all, you are being instructed to do something.

"Building a game that unfolds one small piece at a time is a really, really difficult constraint," says Ingold. "The nag line is a sticking-plaster over that problem."

Is there a solution?

Probably not. On paper, a solution sounds easy. In cinema, if you want to avoid crappy exposition, you are told: "Show, don't tell". In games the equivalent is: "Let do, don't tell". The challenge is that games have to teach how to do - without telling.

Also, many movies still fail to avoid using flashbacks, even to scenes that occurred mere moments ago, so I find it unlikely that videogames' expositiony equivalent in the nag line will evaporate any time soon. The complexity involved in cobbling a game together from the work of various departments, and the imposed limitations of a budget, almost guarantee the nag line's continued existence. But the more players recognise nag lines and moan about them, the more studios will feel required to put effort into either masking them well or learning how to avoid them in the first place.

Maybe. It's also possible we'll just have this same conversation about them in about five years time, the diabolical cycle of discourse churning a full three-sixty once again. Don't worry, I'll nag you to go back and read this article when it all comes up again.

Comments ()