Sword Of The Sea's watery allegory is no great Journey

A popular stereotype of surfers is that they're attractive airheads. A fit waverider doesn't have time for big thoughts, beyond explaining that the moon is, like, totally in league with the whales, man. This is a lame stereotype, and yet a helpful image when it comes to explaining how I feel about dashing surf 'em up Sword Of The Sea. (We don't mind reviewing 5-month old games here at Jank). This game is beautiful, toned, ripped, fashionable, athletic, and it has a great ear for music. It also has the conversational skills of a post-huff stoner, and its visual similarity to Journey only invites an unflattering comparison.

The game itself is an approachable ride. You swoop along in smooth arcs and can leap into the air, double-jumping for extra trick time, cruising through ultimately linear sandy levels that coax you toward lanterns and bells that turn sand into seawater and unlock the way to the next area. It only lasts about 3 hours too, meaning it can glide in and out of your life with unobnoxious merit. If you've got a subscription service that includes the game, there are worse ways to spend an evening.

And there are better. I'd read reviews closer to the game's release that praised it as a "profound" metaphor for climate change, and the ways an individual might fight against that. This feels like the swordfish of style is being mistaken for the sardine of substance. Does the simple idea of restoring water to a desert really Make You Think? Compared to the tension between survival and harvesting in, say, Subnautica or Eco, or the conservational bent of the Shelter series, the seaspreading of this surfer's story feels positively sophomore. As if any of it really makes you ruminate on the great Pacific garbage patch (and that's ages away from the gnarliest waves anyway bro, don't sweat it).

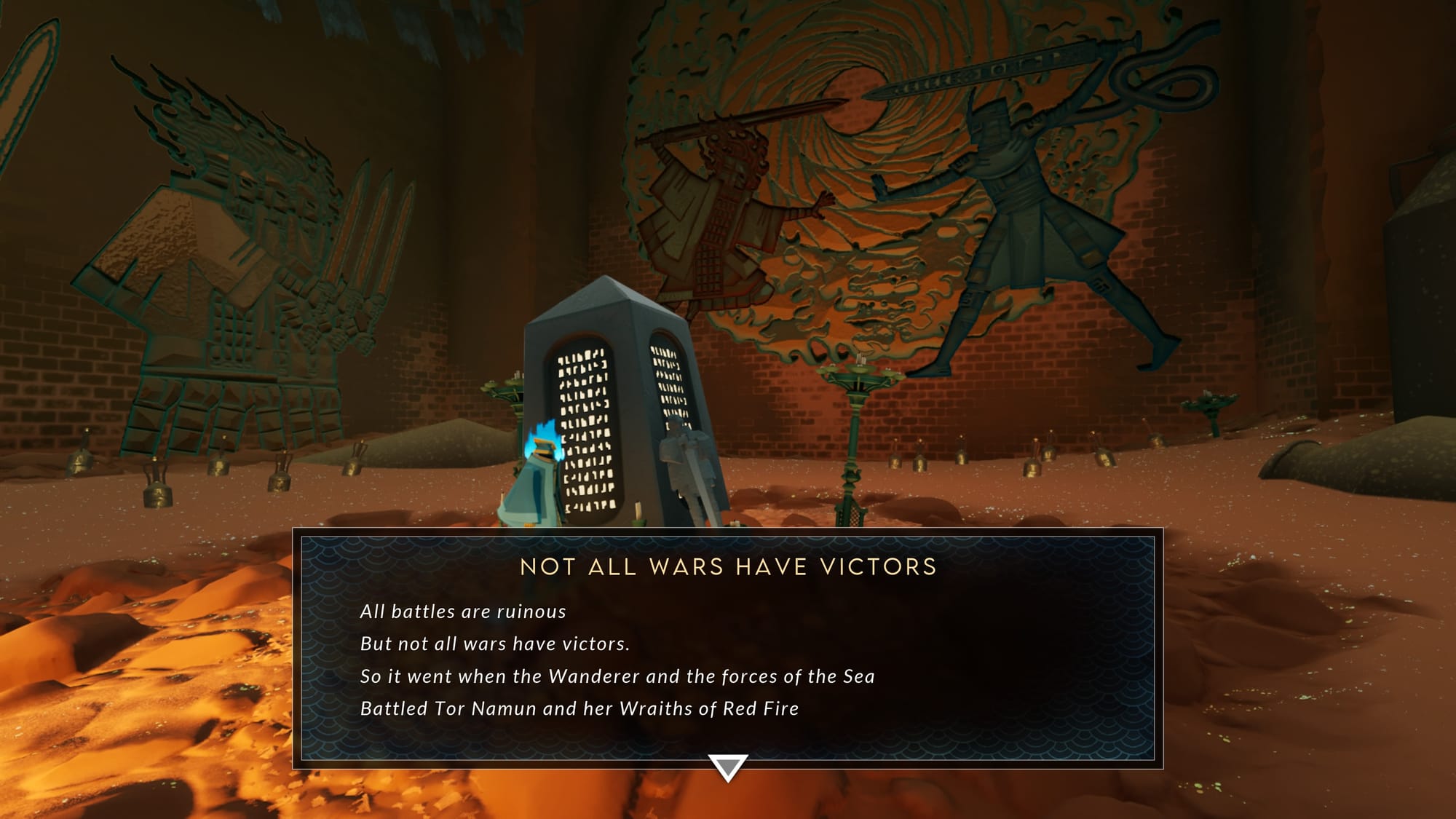

Surfing about, you find rune stones with poems that threaten to teach you the world's history in as obtuse a manner as any lore-delivering stone might do in three stanzas per rock. Some are there to reinforce your goal - to be a "champion" for the sea, and restore it to life. Others wax lyrical about "Farrans" (the people who once lived here) and ancient "ichor", or give a name to a big fire snake that emerges later in the game, called Tor Namun. "Red fire forged her but fury fueled her", we are told of this creature, which is, again, an aesthetically pleasing run of assonance. But doesn't mean much to me aside from communicating there will soon be a big boiling eel to fight.

The same stones sometimes simply tell you to pull a sick trick combo dude, which somewhat undermines the lofty open mic nightness of other runestones.

Three touching poems.

Reading these mineral diaries is like finding the scattered notebook pages of your underemployed but well-meaning friend who's still working out exactly what his collection of slam environmentalism is actually about, and he sometimes just gets tired and writes instructions about how to pop a sweet ollie instead. All videogames continue to be comedy, whether they like it or not.

This is characteristic of how Sword of the Sea makes me feel. It might be an evolution of Journey's visual splendour (it shares an art director and consistently engineers similar beautifully composed vistas) but that doesn't make it an evolution of Journey's soul.

What was the most memorable part of Journey for you? Was it the bit where you clung, tragic and trembling, to your anonymous partner - a real person from across the planet - as both of you slowly froze to a sorrowful stillness in the heights of a mountain pass after an entire night of travelling, chime by chime, across a strange new land together? Or was it, like, totally the sand surfing bit, dude.

Sword of the Sea has double jumps, a bankable currency, boss fights, boost power-ups, and escape sequences. You can later unlock a speedometer, so you can tell when you are lavasurfing downstream at 70 mph. It is a video game in all the ways that Journey was not. It is, for the game literate, visually resplendent, a luscious saunter of wave and wonder, a soothing sonic bath, yet ultimately lacks the complete commitment to an otherworldly experience in the way thatgamecompany's scarf-growing wanderer did.

It's not that one is somehow better than the other (you might be forgiven for playing Journey today only to think: "what's all the fuss about?") but where one game seemed to have an artistic thesis - and damn the lack of gameiness! - the other treats our modern language of game design as something unavoidable, marketable, and safe. Who knows, Sword of the Sea might be correct in this. You certainly could make something like Journey today, but you might not get front row displays on the PS5 catalogue and the requisite hundreds of thousands in marketing money for a Summer Game Fest trailer.

Sliding across water makes you surf faster than on sand. Your surfer will put their hands behind their back when speedy, like a longboarder bombing down a hill. The animation, colour, music, and rising choirs all affirm with expensive strength of spirit that, wow, this is undeniably a work of art. The Assyrian-like stone reliefs of ancient surfer dudes which decorate the sandstone walls are particularly good looking. And yet, there is a central superficiality to the trio of hours spent riding these waves. Compare this to the recent Skate Story, which has both a similarly stylish artblast with at least some of the thematic rigour and depth that Swordsea lacks.

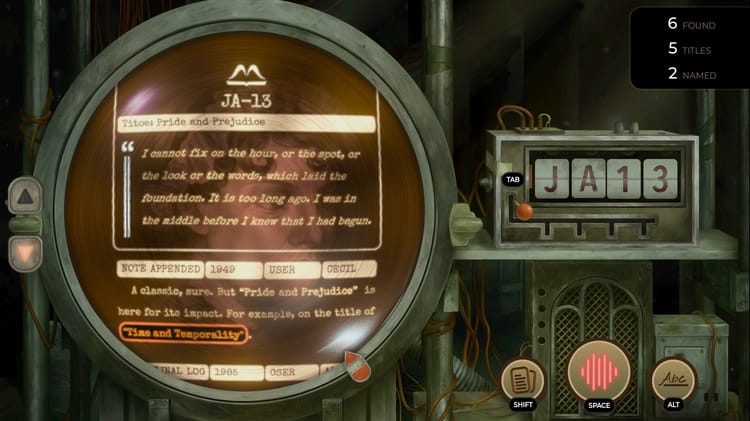

Not to mention a sense of humour. Where Skate Story's dialogue can sometimes be equally superfluous, it is at least often funny and mesmerising, whereas the loreboulder poetry in Sword of the Sea is dry and detached from the game's action. They are little myths reported in too much text with too little significance to your surfing life. Journey's pictogram storytelling of a civilisation brought low by greed for natural resources was pretty on-the-nose, but at least it was succinct, silent, and felt embedded into its world and history. Both games offer a pseudomythic lore dump in the middle of a fancy platformer, but only one of them feels effective.

But it's more than that. What Journey made you feel in travelling next to an online partner was subject to your ideas about companionship, or simply your feelings on buddying up online. When Sword Of The Sea introduces an NPC gal pal, and then shows you her being gobbled alive by a serpent, like a gummy bear thrown into the mouth of a labrador, it cinematizes what was in Journey a personal "friendship" that could end at any moment. I didn't feel much when this sk8r lass was swallowed whole. But when I lost track of my mysterious partner in Journey, the unease was immediate and real. Journey is essentially Attachment Theory: The Videogame. There is sometimes more power in an online hangout, however brief, wordless, and passing, than there is in a cutscene of a pretty-eyed sword surfer.

The gamier Sword-o-Sea gets, the more meaning seems mined away. By the time I was doing basic-as-bread platformer puzzles, and Crash Bandicoot escape sequences, I was emotionally checked out. The high-tempo climactic boss fight at the game's close is an unchallenging circle-surf inside a tunnel where you lob energy bombs and smash a defensive button against quicktimey assaults. It's an eyelash fluttering game, the kind of thing that gets called "evocative" by people who cannot then tell you exactly what it evokes. A refined and professionalised nepo baby of a game, wearing the arty scarf of its forefather Journey yet lacking the same emotional weight. That doesn't make it a total loss - it's a fine three hours - I simply feel the need to kick the hype down a flight of stairs.

At the end of the game, you are given a score, based on clear time and a multiplier, and offered to start New Game Plus. I have not felt the need to play Journey since I first went through it in 2012. Its brevity and thematic strength remains clear in my memory. I don't expect to play Sword of the Sea again either, yet my memory of its dunes is already falling away like dry sand in an hourglass.

Comments ()